Interactive Dashboard: Civilian Targeting in West Africa

September 27, 2024

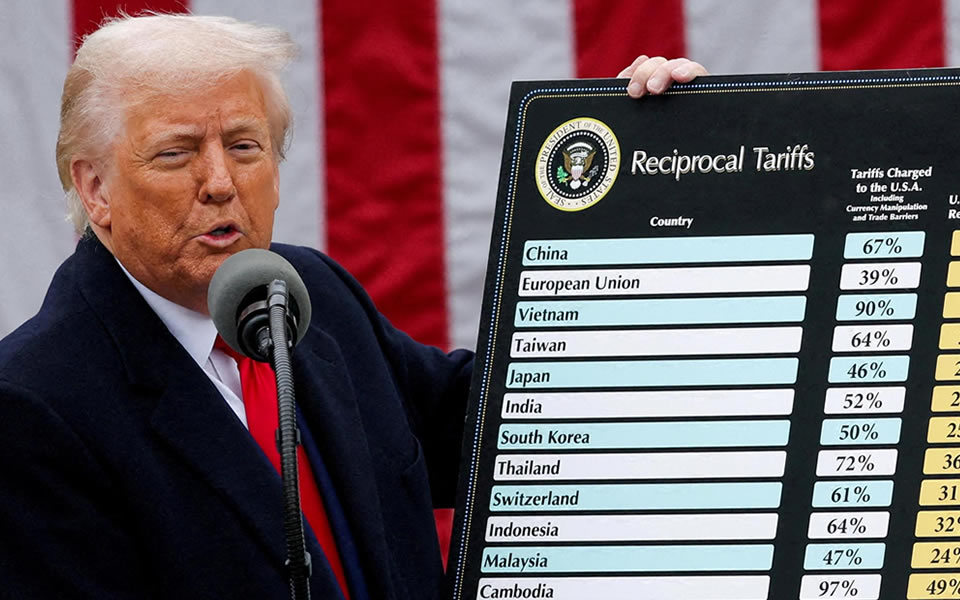

The Impact of Trump’s Tariffs on Africa

April 8, 20252025 WEST AFRICA POLITICAL & SECURITY ASSESSMENT & FORECAST

What You Should Know

- Jihadist groups are expanding their operations beyond the Sahel, with organisations like Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) increasingly targeting coastal states such as Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, and Benin.

- Political instability and military coups have become a recurring challenge in Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Guinea, where military regimes prioritise power consolidation over democratic transition, resulting in fragile governance structures.

- Nigeria remains pivotal to regional stability but faces overlapping crises, including the Boko Haram insurgency, banditry, communal violence, separatist movements, and worsening economic conditions that heighten the risk of civil unrest.

- Economic hardship and social inequality are driving public discontent, with rising inflation, high youth unemployment, and inadequate social services contributing to a wave of protests and strikes across the region.

- Regional bodies and international actors are recalibrating their approaches as the withdrawal of MINUSMA and the increasing influence of non-traditional actors like Russia’s Wagner Group reshape West Africa’s security architecture.

Military Leader of Burkina Faso, Capt. Ibrahim Traoré (Left) meets President John Mahama of Ghana in January 2025.

Introduction

West African leader meeting at the ECOWAS Summit in August 2023

West Africa is currently confronting an escalating crisis driven by an intricate web of security threats, political instability and deepening economic challenges. The Sahel has become synonymous with insecurity, where jihadist groups exploit weak state control and porous borders to expand their influence. What began as a localised insurgency in northern Mali has transformed into a transnational conflict that now threatens coastal states like Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Benin, and Togo. Combined with a wave of military coups and entrenched economic hardship, West Africa faces one of its most volatile periods in decades.

Jihadist groups such as Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) have evolved into formidable actors, shifting their focus southwards and capitalising on governance vacuums and local grievances. Coastal countries, previously considered bastions of stability, are now grappling with the spread of extremist violence into their northern regions. Meanwhile, military juntas in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have prioritised security over democratic transition, creating a fragile political landscape marked by prolonged instability and contested governance.

Amid this turbulence, regional and international actors are rethinking their strategies. Traditional responses to West Africa’s security crises, such as multilateral peacekeeping and Western military intervention, are giving way to new alliances and localised security initiatives. The recent withdrawal of MINUSMA from Mali and the growing influence of non-traditional actors like Russia’s Wagner Group are reshaping the region’s security architecture. As West Africa navigates this precarious juncture, understanding the evolving dynamics is critical to anticipating the region’s future and identifying opportunities for stability.

Regional Overview

(From Left to Right) Col. Assimi Goïta (Mali), Gen. Abdourahamane Tiani (Niger), Capt. Ibrahim Traoré at the first summit of the Alliance of the Sahel States (AES) in Niger, July 2024.

West Africa’s security and political environment is defined by overlapping crises that threaten to undermine the region’s stability. The Sahel—particularly Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—sits at the epicentre of jihadist violence, with vast territories falling outside effective state control. These countries have become battlegrounds for insurgent groups, notably Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), which exploit weak governance and local grievances to expand their reach. Despite ongoing counterinsurgency efforts, state security forces remain overstretched and under-resourced, struggling to contain the growing threat.

Nigeria, the regional powerhouse, faces a unique set of challenges that are both internal and regional in nature. The country is beset by a constellation of security threats—ranging from the Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast to banditry and communal violence in the northwest and central regions. Separatist tensions in the southeast, driven by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), add another layer of complexity. Political divisions and economic pressures, including inflation, fuel subsidy cuts, and high youth unemployment, have exacerbated public discontent, raising the spectre of civil unrest in urban centres. As the most populous country in Africa, Nigeria’s stability is pivotal to the security of the broader West African region.

Coastal states such as Benin, Togo, and Côte d'Ivoire have seen an uptick in jihadist activity spilling over from the Sahel, despite significant investments in border security. While these countries have avoided large-scale insurgent attacks so far, jihadist incursions into their northern regions highlight the growing fragility of these borders. Ghana and Senegal, long considered regional pillars of stability, are increasingly vulnerable to rising political tensions and growing youth discontent. Recent protests in Senegal over the exclusion of opposition figures from elections reflect an undercurrent of frustration that could escalate if left unaddressed.

Regional bodies like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are facing unprecedented challenges in maintaining cohesion and enforcing democratic norms. The emergence of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), a bloc led by Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, poses a direct challenge to ECOWAS’ leadership in regional security affairs. The withdrawal of the UN peacekeeping mission MINUSMA from Mali has created a security vacuum that jihadist groups have eagerly filled, while the diminishing presence of Western forces has forced regional governments to seek new alliances. As West African states adjust to this evolving security landscape, balancing external support with local resilience will be crucial to avoiding further destabilisation.

Jihadist Expansion & Regional Instability

The Sahel region—spanning Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—remains the epicentre of jihadist insurgency in West Africa, where groups like Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) have transformed into regional actors with ambitions beyond the Sahel. These groups have capitalised on porous borders, weak governance, and the withdrawal of Western military forces to expand their operations southwards. Their growing presence in the northern regions of coastal states such as Benin, Togo, and Côte d'Ivoire represents a significant shift, turning areas once seen as stable into new frontlines of conflict.

Jihadist groups have refined their tactics to adapt to this evolving theatre of operations. No longer confined to rural ambushes and highway attacks, they have begun using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and sophisticated propaganda campaigns to undermine state control and radicalise local communities. The southern expansion is strategic—jihadists seek to establish footholds in resource-rich regions and disrupt trade routes connecting the Sahel to coastal cities. In northern Benin and Togo, cross-border raids and attacks on security posts have increased, forcing governments to reallocate military resources and stretch their already limited capacities.

Local grievances have provided fertile ground for jihadist recruitment and influence. In many affected regions, weak state presence, economic marginalisation, and competition over resources—particularly land and water—fuel tensions between communities. Jihadist groups have exploited these divisions, presenting themselves as protectors or alternative sources of governance. In Burkina Faso and Mali, jihadists have established shadow administrations, taxing local populations and providing a rudimentary form of justice, further eroding state authority. As they push south, they are likely to replicate these tactics, particularly in underdeveloped and politically neglected border areas.

The response from regional governments has been mixed. While coastal states have taken proactive measures to secure their northern borders, including joint operations under the Accra Initiative, their efforts are constrained by limited intelligence-sharing, insufficient resources, and the fragmented nature of regional security frameworks. The reliance on community militias, such as Burkina Faso’s Volontaires pour la Défense de la Patrie (VDP), has provided short-term security gains but also risks fuelling cycles of communal violence and human rights abuses. Unless regional states develop a more coordinated and well-resourced strategy, the steady southward expansion of jihadist groups will continue to destabilise large parts of West Africa.

Political Instability & Military Coups

There were #Endbadgovernance Protests across Nigeria in November 2024

In recent years, West Africa has experienced an alarming rise in military coups, reflecting deep-rooted dissatisfaction with governance, widespread insecurity, and economic hardship. Since 2020, six coups have occurred in Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Guinea, signalling a shift toward authoritarian military regimes. These juntas have justified their actions by citing the failure of civilian governments to manage growing security threats and address socio-economic grievances. However, their focus on consolidating power rather than implementing genuine reforms has left these countries vulnerable to prolonged political instability. Efforts to restore civilian rule have been slow, with transition timelines frequently extended or ignored, creating frustration among civil society groups and further isolating these regimes from regional and international partners.

The proliferation of military governments has posed a serious challenge to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which has struggled to enforce democratic norms and manage political transitions. The recent emergence of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—a bloc of military-led governments in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—has weakened ECOWAS’ influence and raised the risk of further regional fragmentation. While countries like Senegal, Ghana, and Côte d'Ivoire have maintained relative political stability, even these states face rising political tensions due to contested elections, youth discontent, and unresolved socio-economic grievances. Without meaningful political reforms and a renewed commitment to democratic governance, West Africa is likely to experience continued instability, further complicating regional security efforts and economic recovery.

Regional & International Responses

The response to West Africa’s growing instability has been shaped by a combination of national efforts, regional cooperation, and international engagement. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has been at the forefront of diplomatic and security interventions, imposing sanctions on coup regimes and coordinating regional efforts to uphold democratic norms. However, its capacity to enforce compliance has been limited, particularly in the face of defiant military regimes in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. The emergence of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) has further weakened ECOWAS’ cohesion and complicated regional security coordination. Meanwhile, initiatives such as the Accra Initiative, focused on enhancing cross-border security among coastal states, offer a more pragmatic approach to addressing the spread of jihadist violence.

International actors have recalibrated their roles in the region, shifting from direct intervention to more advisory and capacity-building roles. France’s withdrawal from Mali and the subsequent end of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) left a security vacuum that jihadist groups have eagerly exploited. While France has repositioned its forces in neighbouring countries such as Niger and Chad, anti-French sentiment across the region has complicated its engagements. The United States, through AFRICOM and the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership (TSCTP), continues to provide intelligence support and military training, but its footprint remains limited. Meanwhile, non-traditional actors like Russia’s Wagner Group and Turkey have increased their presence, offering security assistance to regimes that feel alienated by the West. This evolving security landscape underscores the need for stronger regional cooperation and more balanced international engagement to prevent further fragmentation and conflict.

Non-State Actors & Their Influence

Non-state actors have become significant players in West Africa’s security and political landscape, operating as both stabilising and destabilising forces. Jihadist groups, such as Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), represent the most immediate threat. These groups exploit weak state presence and local grievances to expand their reach, establishing parallel systems of governance in rural areas. Their strategy goes beyond military operations; they seek to control local economies, tax communities, and impose their version of justice. As they expand into coastal states, jihadist groups are increasingly blending with local conflicts, making them harder to dislodge.

In response to state inaction or inability to provide security, community militias and self-defence groups have proliferated across the region. In Burkina Faso, the Volontaires pour la Défense de la Patrie (VDP) were established as civilian auxiliaries to support the military’s counterinsurgency efforts. While they have provided some security, their lack of training and allegations of human rights abuses have made them a double-edged sword. Traditional groups like the Dozo hunters and Koglweogo militias often act as local enforcers but are frequently implicated in ethnic violence and cycles of retaliation. Meanwhile, criminal networks involved in arms smuggling, human trafficking, and drug trade have taken advantage of porous borders to expand their operations, further eroding state authority and fuelling conflicts across the region.

Civil society and political opposition groups also play a vital role, particularly in coastal countries like Nigeria, Senegal, and Ghana, where they advocate for greater accountability and democratic reforms. Movements such as Nigeria’s #EndSARS campaign have mobilised thousands in protests against police brutality and poor governance. Youth-led activism is growing across the region, fuelled by frustration with unemployment and economic hardship. Although these movements often face state repression, they represent a powerful force for change in countries where traditional opposition parties have been weakened or co-opted.

Separatist movements and ethnic militias add another layer of complexity to West Africa’s already fragile security environment. In Nigeria’s southeast, the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) continue to push for secession, while Senegal’s Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC) remains active in its long-running campaign for autonomy. Although weakened, these movements strain government resources and complicate national security strategies. As non-state actors become increasingly embedded in local conflicts, the challenge for regional governments will be to contain their influence while addressing the grievances that give rise to them.

Socio-Economic Drivers of Instability

Economic fragility is a critical factor exacerbating instability across West Africa. Persistent poverty, high youth unemployment, and rising inflation have deepened public frustration and heightened tensions in already fragile states. Conflict in the Sahel has disrupted agricultural production, leading to severe food insecurity in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. In Nigeria, dwindling oil revenues, inflation, and the removal of fuel subsidies have strained government resources and sparked widespread protests. These economic pressures have particularly affected urban youth, who face limited job opportunities and shrinking prospects for social mobility. The situation is worsened by weak social services and corruption, leaving many feeling abandoned by the state and turning to protests, civil disobedience, or, in some cases, armed groups for protection and survival.

Public discontent has manifested in growing waves of social unrest across the region. In Senegal, protests triggered by political grievances have increasingly taken on an economic dimension, with demands for improved governance and social reforms. Meanwhile, in Nigeria, mass demonstrations like the #EndSARS movement have highlighted deep-rooted frustrations with systemic corruption and police brutality. The combination of worsening economic conditions and growing youth activism is likely to increase the frequency and intensity of protests in the coming years. If left unaddressed, these socio-economic challenges will not only fuel instability but also provide fertile ground for extremist recruitment and political violence, further destabilising the region.

Scenarios & Regional Forecast

Prolonged Transitions & Weak Governance in Coup-Affected States

Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Guinea are expected to experience extended transitional periods with minimal progress toward civilian-led governance. Military regimes in these states will prioritise internal security and consolidation of power over meaningful democratic reforms. The absence of political dialogue with opposition groups and civil society will deepen internal tensions, creating an environment of fragile governance. ECOWAS will continue to struggle in enforcing compliance with transition timelines, further eroding its influence. As a result, authoritarian structures will persist, leaving these states highly vulnerable to social unrest and political instability.

Expansion of Jihadist Influence Beyond the Sahel

Jihadist groups such as Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) will likely continue their expansion beyond Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger into coastal West African states such as Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, and Benin. The frequency of security incidents in these border regions will increase, with jihadist groups exploiting local grievances and weak state presence to establish new footholds. The rise in cross-border attacks and the increased use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) will present significant challenges for security forces in these coastal states, further straining already fragile communities along the northern borders.

Growing Role of Militias & Community Defense Groups

The inadequacy of state security in remote regions will drive communities to rely increasingly on self-defence militias such as Burkina Faso’s Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP), Koglweogo, and the Dozo hunters. While these groups offer immediate security in areas neglected by the state, their presence risks escalating intercommunal conflicts and contributing to cycles of reprisal violence. Human rights abuses by militias—particularly in Burkina Faso and northern Mali—will complicate regional stabilisation efforts and undermine state legitimacy, making long-term security improvements more difficult.

Continued Political Tensions & Economic Strain in Nigeria

Nigeria will face persistent security challenges, particularly in the northeast and northwest, where Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) continue to operate. Banditry, communal violence, and kidnapping-for-ransom will remain pervasive in the northwest and Middle Belt. Politically, tensions are likely to persist following the country’s most recent elections, exacerbated by worsening economic conditions driven by inflation, fuel subsidy cuts, and currency devaluation. Public frustration with these issues will likely result in widespread protests and labour strikes, especially in urban centres, creating further instability.

Limited International Engagement & Regional Self-Reliance

The withdrawal of MINUSMA from Mali and the declining presence of Western forces across the Sahel will force regional states to rely increasingly on domestic military capacities and regional initiatives. The Accra Initiative, which aims to boost cross-border cooperation among coastal states, is expected to gain prominence in countering the spread of jihadist influence. However, without substantial external support and sustained international engagement, the ability of these countries to contain the threat will be limited, leaving key border areas exposed to further destabilisation.

Conclusion

West Africa is at a pivotal moment, facing a convergence of security, political, and socio-economic challenges that threaten to destabilise the region further. The Sahel remains the epicentre of jihadist insurgency, with militant groups expanding their reach into previously stable coastal states. Military regimes in Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Guinea show little progress toward democratic transition, prioritising internal security and survival over meaningful reform. This governance vacuum, coupled with economic hardship and growing public discontent, continues to fuel unrest and undermine state authority. Without immediate and coordinated responses, the region risks deeper fragmentation and prolonged conflict.

Despite these challenges, there are opportunities for regional resilience. Initiatives such as the Accra Initiative and strengthened cooperation between West African states offer a framework for addressing cross-border threats. However, regional governments must focus on improving governance, restoring civilian rule, and addressing the socio-economic drivers of instability to ensure long-term stability. External actors will remain essential, but the success of any effort will ultimately depend on the capacity of West African nations to lead the response. A combination of targeted security strategies, political reform, and economic investment will be critical in preventing further deterioration and charting a path toward peace and stability in the region.