The Impact of Trump’s Tariffs on Africa

April 8, 2025

Cote d’Ivoire Decides 2025: Political & Security Forecast

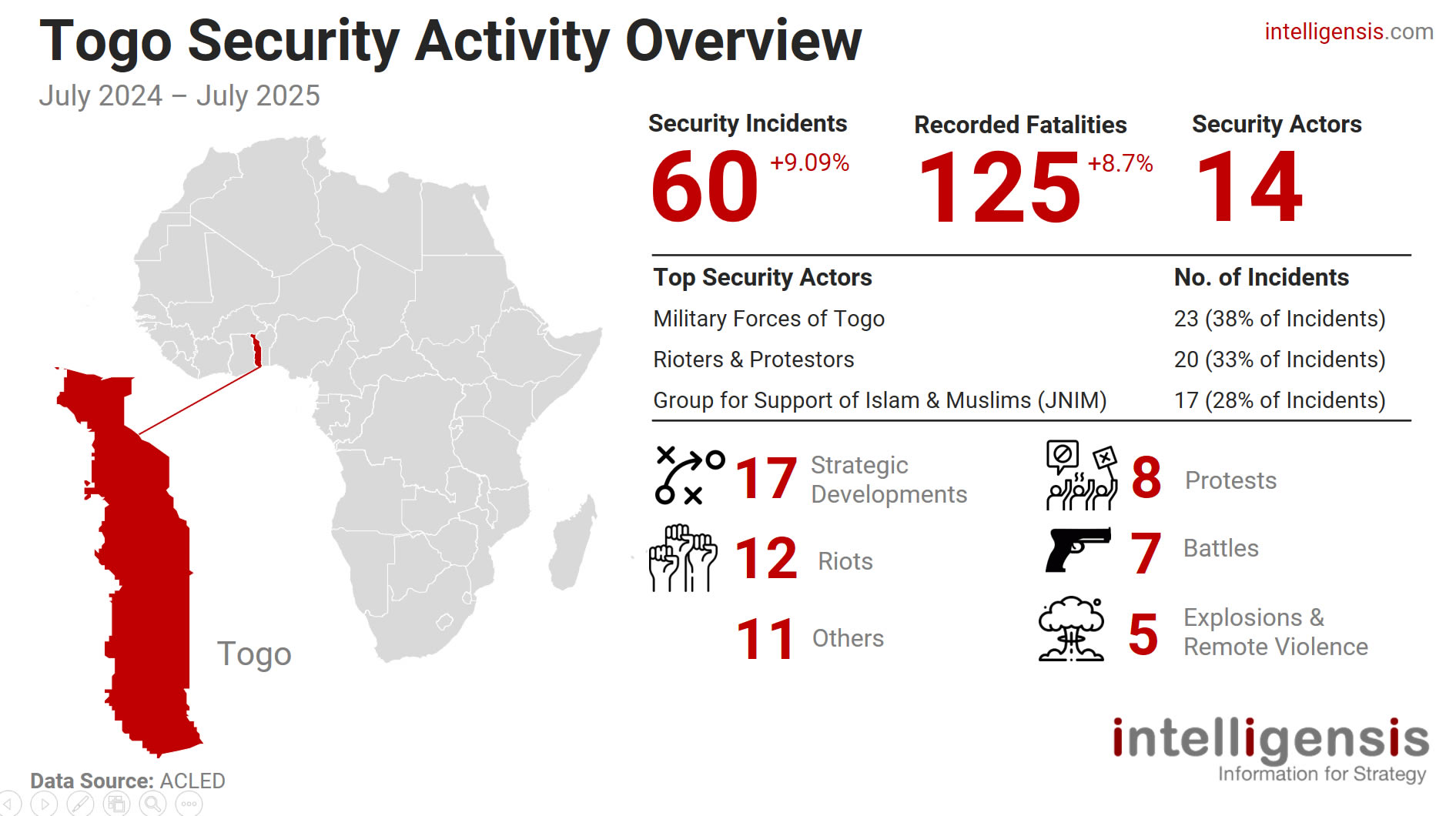

October 21, 2025TOGO’S FRAGILE STABILITY UNDER THREAT

Key Insights

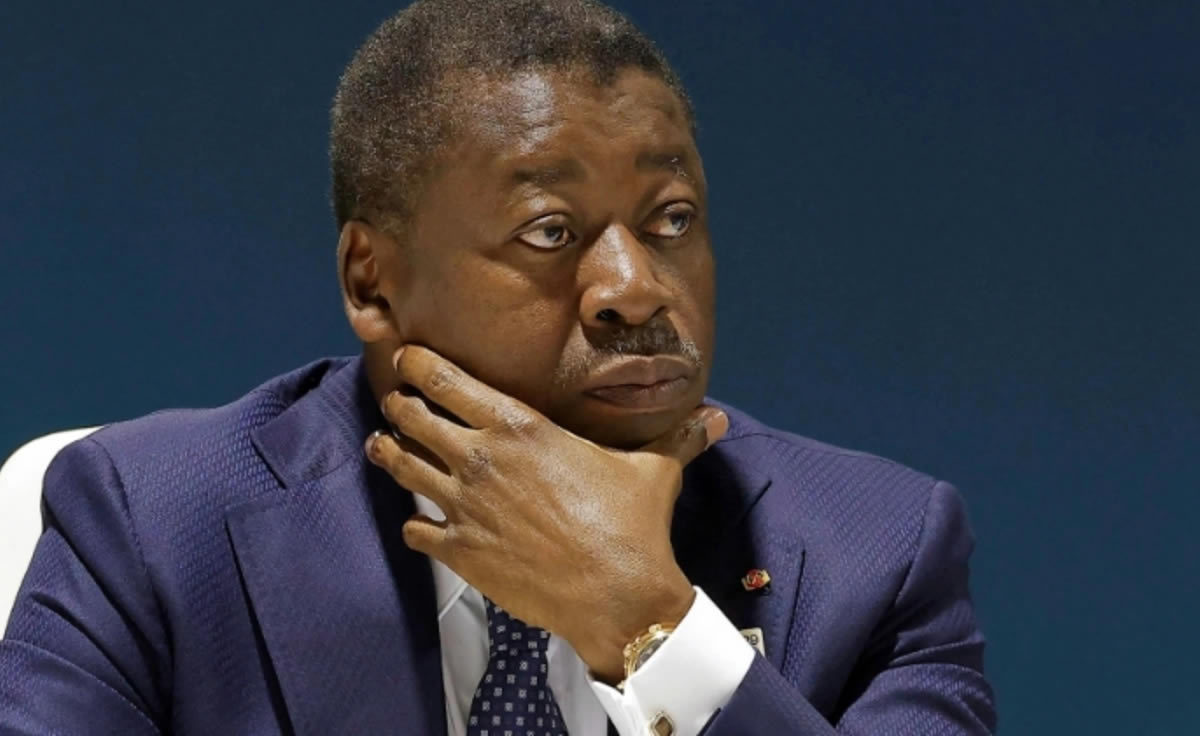

- Togo is undergoing its most serious political crisis in over a decade following controversial constitutional reforms that have entrenched President Faure Gnassingbé’s indefinite hold on executive power.

- Widespread protests in June and July 2025, driven largely by youth and civil society actors, have been met with a violent crackdown resulting in deaths, disappearances, and mass arrests.

- The regime has leveraged state and non-state security actors including unregistered militias, to suppress dissent and maintain control through repression and information blackouts.

- The opposition remains fragmented and marginalized, while regional and international responses, including from ECOWAS, have so far been limited and cautious.

- Without meaningful structural reform, the current suppression strategy is likely to provoke recurrent unrest and accelerate the regime’s legitimacy crisis in the medium to long term.

Summary

Togo is facing an intensifying political crisis following the April 2024 adoption of a new constitution that replaced direct presidential elections with a parliamentary system, allowing long-time ruler Faure Gnassingbé to consolidate power indefinitely as President of the Council of Ministers. This political reconfiguration, widely viewed as a “constitutional coup,” has triggered waves of protest and civil unrest, particularly between June and July 2025, led by youth-driven movements and civil society coalitions. The government has responded with sweeping repression, including arbitrary arrests, internet shutdowns, the use of live ammunition, and alleged extrajudicial killings.

Despite maintaining operational control over state institutions and the security apparatus, the Togolese regime faces a growing legitimacy deficit, exacerbated by socioeconomic grievances, demographic shifts, and international scrutiny. Regional and international actors have condemned the violence but stopped short of direct intervention. In the likely scenario where repression quells immediate unrest without addressing root causes, future instability remains probable. Alternatively, a less likely path could emerge if sustained pressure compels the regime toward reform and negotiated political opening.

Background

Togo, a small West African nation with a population of approximately 9 million, has been ruled by the Gnassingbé family since 1967. Following the death of long-time autocrat Gnassingbé Eyadéma in 2005, his son Faure Gnassingbé assumed the presidency amid a contested and violent transition. Despite periodic elections and nominal multiparty competition, the Togolese political system has remained dominated by the ruling Union for the Republic (UNIR) party, underpinned by a patronage-based regime architecture, the coercive apparatus of the state, and a heavily centralized executive branch. Over the past two decades, the regime has faced recurrent domestic and international criticism over its authoritarian tendencies, curtailment of civil liberties, and manipulation of constitutional norms to extend Faure Gnassingbé’s rule.

In April 2024, a controversial new constitution was adopted, replacing the semi-presidential system with a parliamentary one. The reform eliminated direct presidential elections and transferred executive authority to a newly created position, President of the Council of Ministers, effectively allowing Faure Gnassingbé to maintain indefinite power by parliamentary reappointment. This “constitutional re-engineering” was widely perceived as a power grab and was swiftly followed by the May 2025 appointment of Faure to this new executive role. The change triggered significant unrest, culminating in a wave of protests in June and July 2025, led predominantly by youth and civil society actors outside the traditional political opposition. The crackdown that followed has been marked by reports of torture, abductions, disappearances, and at least seven confirmed deaths. In addition, the Gnassingbé-led government’s response to the protests has drawn international attention and condemnation, setting the stage for a serious legitimacy and governance crisis in a country already facing deep socio-political fatigue.

Key Actors

The current political crisis in Togo is being shaped by the actions and interactions of five primary categories of stakeholders: the ruling regime and its institutions, civil society protest networks, opposition parties, state-aligned coercive entities, and external international and regional actors. Each group possesses distinct interests, capabilities, and constraints, and together they form the contested political landscape in which legitimacy, control, and accountability are being fiercely contested.

Government of Togo

The Togolese government, under the leadership of Faure Gnassingbé and the ruling Union for the Republic (UNIR) party, has pursued a deliberate strategy of constitutional reform to maintain long-term political dominance. It continues to assert that the new political structure represents institutional modernization, while rejecting accusations of usurping power. The regime has relied on institutional control, security coercion, and legal restrictions to suppress dissent and preserve authority.

Civil Society and Protest Movements

Civil society actors, including the “Touche pas à ma Constitution” movement, diaspora influencers, and youth-led digital activists, have emerged as key challengers to the regime's legitimacy. These groups operate both domestically and transnationally, using protest mobilization, social media advocacy, and calls for international pressure. Their demands centre on democratic restoration, constitutional reversal, and accountability for human rights violations.

Opposition Political Parties

Togo’s formal opposition parties, including the National Alliance for Change (ANC), Alliance of Democrats for Integral Development (ADDI) and the Democratic Forces for the Republic (FDR), have denounced the constitutional changes but remain structurally marginalized by the ruling party’s dominance over electoral institutions and the security apparatus. While involved in protest coordination and legal challenges, their political capital remains weak, and internal fragmentation has limited their ability to lead a unified resistance. Some factions continue to push for inclusive national dialogue and a return to the 1992 constitution.

Security Forces & Auxiliary Groups

The Togolese Armed Forces, police, gendarmerie, and affiliated informal militias have played a decisive role in regime preservation through the suppression of civil dissent. Armed personnel have been deployed across Lomé with reports of house raids, use of live ammunition, and collaboration with masked, unregistered auxiliaries engaged in beatings, abductions, and intimidation. This coercive alliance has created a climate of impunity and fear, raising serious concerns about unlawful use of force and extrajudicial practices.

International & Regional Actors

International actors including Amnesty International, Reporters without Borders, and the Togolese diaspora have condemned the repression and called for independent investigations into abuses. ECOWAS has thus far maintained a cautious stance, avoiding direct condemnation but expressing concern over democratic backsliding and instability. Meanwhile, the suspension of France 24 and RFI illustrates the regime’s efforts to limit foreign media scrutiny and control the narrative surrounding the crisis.

Analysis

The ongoing unrest in Togo reflects the culmination of long-standing authoritarian entrenchment, structural democratic erosion, and deepening generational discontent. The current unrest is not merely reactive to the constitutional changes but indicative of systemic fragilities within Togo’s governance model—marked by dynastic succession, repression of dissent, and elite insulation from popular will. While the regime maintains short-term control through security dominance and institutional capture, the social, demographic, and political undercurrents now coalescing around popular resistance suggest a more volatile and uncertain trajectory ahead.

Governance & Power Consolidation

Faure Gnassingbé’s transition to the role of President of the Council of Ministers represents a deliberate constitutional maneuver to circumvent presidential term limits and extend his rule under a new legal framework. This move, executed via a parliamentary process devoid of public consultation, has further centralized executive authority while simultaneously eroding citizen trust in representative institutions. The regime’s long-term strategy appears oriented toward formalizing dynastic succession within a controlled legal architecture, rather than engaging in genuine power-sharing or reform.

Security Force Posture & Use of Force

The posture of Togolese security forces has shifted toward a doctrine of deterrence through overwhelming force, characterized by pre-emptive deployments, the use of tear gas, live ammunition, arbitrary arrests, and collaboration with irregular auxiliary units. This strategy has effectively suppressed short-term dissent but has also intensified public animosity and further delegitimized the regime’s claims to order and legality. The lack of accountability mechanisms and the use of extrajudicial tactics risk provoking further radicalization among protest movements.

Structural Weaknesses in the Political System

Togo’s political architecture is marked by overconcentration of power in the executive, weak institutional independence, and limited checks on authority, resulting in chronic democratic deficits. Electoral processes are widely perceived as manipulated, and opposition parties face structural exclusion through legal, administrative, and coercive means. This institutional fragility renders the system vulnerable to legitimacy crises whenever the ruling elite overreach or confront rising public expectations.

Youth Discontent

A generational shift is driving much of the current mobilisation, with urban youth rejecting the entrenched political order inherited from the post-colonial era. Disillusionment with elite patronage, lack of economic opportunity, and generational memory of repression has catalysed new modes of digital activism, protest coordination, and diaspora engagement. This youth-led resistance represents an increasingly organised force that is ideologically distinct from the older political class and may prove more resilient and adaptive in sustained contestation.

Implications

The intensification of political unrest in Togo has significant implications for regime durability, domestic security, and regional diplomatic posture. While the government has succeeded in asserting short-term control through coercive means, it faces mounting legitimacy deficits and increased pressure from both domestic constituencies and international observers. The crisis is unfolding against a backdrop of heightened regional sensitivity to unconstitutional rule and state fragility, raising concerns over the potential spillover of instability in a sub-region already beset by political volatility.

Government & Regime Stability

The Togolese regime remains structurally stable in the immediate term due to its control over the security apparatus, the judiciary, and legislative institutions. However, the consolidation of power through constitutional manipulation has exacerbated public disenchantment, especially among urban youth, weakening the long-term social contract between the state and citizenry. Without credible reform or genuine dialogue, the regime’s legitimacy crisis is likely to deepen, creating latent vulnerabilities to both civil unrest and elite fracture.

Internal Security Dynamics

The security environment is increasingly strained, with the recurrent deployment of force against civilians risking overextension of security forces and eroding public cooperation in intelligence gathering. The involvement of irregular auxiliary groups and allegations of extrajudicial actions could further destabilize the internal order by fostering radicalization and mistrust of state institutions. If protest activities evolve into sustained resistance networks or adopt asymmetric tactics, the state could face a more protracted and unpredictable internal security challenge.

Regional & Diplomatic Repercussions

Togo’s trajectory toward authoritarian consolidation places ECOWAS in a difficult position as it seeks to uphold constitutional norms in the region while avoiding another confrontation with a member state. Regional actors have thus far adopted a cautious approach, but continued repression or escalation of violence could trigger formal diplomatic responses, including targeted mediation or sanctions. International watchdogs and bilateral partners are increasingly vocal, and sustained abuses may isolate the regime diplomatically and jeopardize development cooperation frameworks.

Forecast

Togo’s political outlook remains precarious, shaped by the evolving balance between state repression and public resistance. While the government retains operational control through its security forces and institutional dominance, the persistence of protests, growing youth mobilization, and increasing international scrutiny suggest that the crisis is far from resolved. The medium-term trajectory hinges on whether the ruling elite remains committed to authoritarian consolidation or is compelled—by internal or external pressure—to engage in substantive reform. Two scenarios are assessed below:

Scenario 1: Government Successfully Suppresses Current Protests (More Likely)

The regime is likely to maintain its grip on power in the short term through sustained coercive measures, media control, and internet restrictions, but absent structural reforms, the underlying grievances will persist and may resurface in future waves of unrest, potentially with greater intensity and organisation. A continuation of the current strategy of violent repression will eventually erode the legitimacy of the Gnassingbé-led government, resulting in its collapse over the medium to long term.

Scenario 2: Protesters Able to Effect Meaningful Change (Less Likely)

A less probable outcome would see sustained domestic mobilization, combined with coordinated opposition and international diplomatic pressure, forcing the regime to make concessions such as initiating dialogue, reversing elements of the constitutional reform, or allowing limited political liberalization.